Photo from wikipedia

565 which was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; 1,200 copy/mL). Two months later, the clinical examination of the eightmonth-old boy was normal. Anti-CMV IgG were detected but anti-HSV and… Click to show full abstract

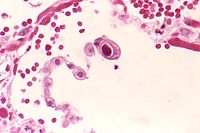

565 which was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; 1,200 copy/mL). Two months later, the clinical examination of the eightmonth-old boy was normal. Anti-CMV IgG were detected but anti-HSV and anti-VZV antibodies were not present, and PCR blood test for enterovirus was negative. The mother was CMV IgG seropositive but was negative before her pregnancy. No immune deficiency was found. The complete blood count was normal with no Howell-Jolly body. Lymphocyte immunophenotyping and testing for quantitative immunoglobulin including total IgE, chemotaxis of polynuclear neutrophils, and complement component were normal. Natural IgG anti-A antibodies were negative. The diagnosis of KVE is mainly based on clinical history of AD and specific umbilicated erythematous vesicles. The culture and PCR leads to identification of the virus, most commonly HSV. It was thus unexpected in our case to detect CMV and not HSV as anticipated. To our knowledge, no previous case of KVE due to CMV has been reported [1, 2]. Although vesicles were positive for CMV based on both culture and PCR, HSVand other virus-related KVE could not be formally excluded since cutaneous PCR for these viruses was not performed. However, the absence of anti-HSV and anti-VZV IgG and the absence of enterovirus DNA in blood makes this hypothesis unlikely. A CMV primary infection should also be discussed as suggested by the presence of hard palate erosion [1]. However, KVE can also be associated with viremia and involvement of the lungs, liver, brain, gastrointestinal tract and mucosa [3]. Furthermore, based on the unaffected skin with regards to vesicles which involved only pre-existing sites of atopic dermatitis, a CMV superinfection of pre-existing AD seems more likely. Recently, Drozd et al. [1] analysed 53 cases of cutaneous CMV. Manifestations were polymorphous including morbilliform rash, petechiae, purpura, plaques, vesicles, bullae, erosions, erythema, papules, oedema, vasculitis, and pustules. However, ulcers, mainly mucosal, were the most reported lesion. Systemic manifestations of CMV have been described including pneumonitis, gastrointestinal, retinitis, hepatitis and aseptic meningitis [2]. It should be noted that our child presented with intestinal and pulmonary symptoms before the occurrence of cutaneous lesions in association with the presence of anti-CMV IgG. We can thus hypothesize a primary systemic CMV infection as suggested by the CMV seroconversion of his mother during pregnancy or soon after childbirth, followed by a delayed cutaneous infection. The transplacental transfer of maternal anti-CMV IgG to the child can indeed be excluded at eight months of age. Although valganciclovir or ganciclovir are mainly used in the literature to treat cutaneous CMV manifestations [1], acyclovir was successfully used in our experience. Acyclovir is a guanosine-analogue with activity against a range of herpesviruses. It is particularly active against herpes simplex virus-1 and -2, but also has some activity against CMV [4, 5]. KVE should be added to the list of less common dermatological presentations of CMV infection.