Photo from wikipedia

Renal dysfunction is common in patients awaiting a liver transplant, and although often potentially reversible, simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation (SLKT) is indicated in some recipients. Since adoption of Model for End-Stage… Click to show full abstract

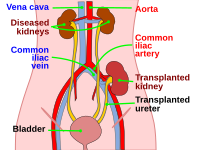

Renal dysfunction is common in patients awaiting a liver transplant, and although often potentially reversible, simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation (SLKT) is indicated in some recipients. Since adoption of Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score allocation in 2002, the annual rate of SLKT has tripled from 134 patients in 2001 to more than 500 patients in 2014 in the United States. The quality of kidneys used for SLKT is also significantly better than those used for kidney transplant alone. Approximately half of the kidneys used in SLKT in 2014 in the United States had a Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) of< 35%, indicating high-quality organs usually prioritized to pediatric recipients. In the last decade, the number of liver transplants performed in the United States has plateaued as well as the number of listed candidates on the waiting list. However, more wait-list patients were sicker and more died or were deemed no longer viable candidates during this period. This has led to pressure to use organs that would have previously been deemed unsuitable for liver transplant. The use of older deceased donors for liver transplantation has increased significantly worldwide with half of liver grafts in the European Union now obtained from donors age 50 years and over. Although studies on the impact of donor age and liveronly transplant outcomes are mixed, donor age is one of the most important risk factors for kidney transplant graft failure. When older or suboptimal donor organs are offered to potential recipients awaiting SLKT, certain donors may be deemed appropriate from a liver quality standpoint but marginal or inappropriate for kidney transplant. Therefore, transplant teams will be placed in the position of deciding whether to accept a marginal kidney graft in SLKT rather than waiting for a more suitable donor. The decision takes into account the condition of the potential recipient as to whether they can wait for another offer as well as the likelihood of recovery of kidney function after transplant. Data from the United States Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients indicate that kidneys accepted for SLKT are usually of high quality (mean KDPI of 35% with very few kidneys with KDPI over 90%). In some of these higher KPDI kidneys, United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) guidelines (see Table 1) recommend consideration for transplantation as adult dual kidney transplantations (DKTs). In the United States, DKTs are uncommonly performed, with only approximately 100 patients annually with outcomes comparable to extended criteria donor kidneys. In this issue of Liver Transplantation, Di Laudo et al. report a case-control study of 4 patients who underwent liver with dual kidney transplantation (LDKT) and compared them to 11 SLKTs. When “expanded criteria donors” (defined as from a donor over 60 years old with clinical risk factors or from a donor over 70 years old) became available for both liver and kidney donation, biopsies were performed on donor organs to assess suitability. If the liver was accepted, the decision on whether kidneys were used as single or dual was based on the Remuzzi score, which is well established for kidney-only transplants. A Abbreviations: DKT, dual kidney transplantation; KDPI, Kidney Donor Profile Index; LDKT, liver with dual kidney transplantation; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; SLKT, simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation; UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing.

Journal Title: Liver Transplantation

Year Published: 2017

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!