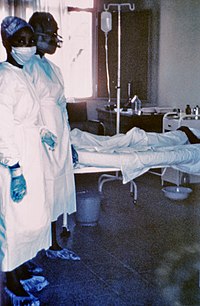

Photo from wikipedia

Ebola virus (EBOV) outbreaks are unpredictable, sporadic, and historically occur in remote locations of equatorial Africa. Traditionally, outbreak control consists of identifying EBOV-infected patients and contact tracing. Ebola treatment centers… Click to show full abstract

Ebola virus (EBOV) outbreaks are unpredictable, sporadic, and historically occur in remote locations of equatorial Africa. Traditionally, outbreak control consists of identifying EBOV-infected patients and contact tracing. Ebola treatment centers provide limited supportive care with rigorous infection control. Communication, education, and establishing trust with the community to allow continued surveillance and altering funeral rituals to ensure safe and dignified burials have been the focus for stopping EBOV spread since its discovery in 1976. High case fatality rates of EBOV infection have justified administering unproven candidate therapeutics, convalescent plasma, or repurposed medicines on a compassionate use basis. In 2014, WHO declared the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (the largest to date) an international public health emergency. Subsequently, international institutes began requesting unproven but promising experimental therapeutics to combat EBOV [1]. Federal and academic research programs had been evaluating candidate therapies in cell culture, small animal, and non-human primate models of EBOV infection, but there had not been a registered clinical trial. While compassionate use guidelines were accepted, ethics of performing clinical trials during an outbreak were heavily debated [2]. Patients’ need for the highest therapeutic benefits precluded placebo controls. Reallocation of limited resources from supportive care was a concern, and sufficient quantities of trial therapeutics were needed. Regulatory, ethical, pharmaceutical, and governmental committees had to be coordinated to approve clinical guidelines, in hindsight causing significant delays in starting trials. The outbreak peaked between August and December 2014, and the earliest trials began in 2015. As case numbers declined, matching location of trial centers with sufficient numbers of infected patients became problematic. Despite these enormous hurdles, diligent scientists insisted that Ebola patients deserved evidence-based effective treatment. Clinical trials were initiated evaluating small molecular inhibitors favipiravir

Journal Title: EBioMedicine

Year Published: 2019

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!