Photo from wikipedia

The past decades have seen an increase in infections of cardiac implantable electronic devices (pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices), and the number of infections appears set… Click to show full abstract

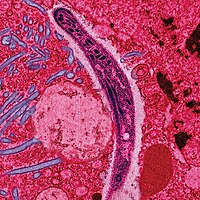

The past decades have seen an increase in infections of cardiac implantable electronic devices (pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices), and the number of infections appears set to increase further. Prominent factors underlying this trend are the growing number of indications for device implantation and the older age of individuals carrying these devices, with the associated burden of accompanying diseases, mainly kidney failure. Physicians who prescribe and fit these devices are duty bound to familiarize themselves with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these infections. Cardiac device infection can be local (pocket infection) or systemic, and device implantation can also provoke local inflammation; distinguishing among these conditions can be challenging (Table). Postimplant inflammation manifests as erythema near the incision site within 30 days of implantation. This inflammation is caused by mechanical injury and can be difficult to distinguish from local infection. Local infection is indicated by signs of infection in the pulse generator pocket, including swelling, pain, purulent discharge, fistula formation, and skin erosion with or without device extrusion. Device extrusion is always a sign of infection. Systemic infection is further accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, shivering, a blood count typical of bacterial infection, and sometimes a positive blood culture. Systemic infection accompanied by vegetations in the device leads or any of the right valves indicates device endocarditis, which is also increasing, both in absolute patient numbers and as a percentage of the total number of right endocarditis cases. Once a diagnosis is confirmed as local infection, systemic infection, or endocarditis, it is crucial to act fast; the entire apparatus, including the pulse generator and leads, must be removed as soon as possible. The most frequent infecting microorganisms are coagulase-negative staphylococci, which are typical in infections of foreign material. These microorganisms are highly adherent, frequently form biofilms that make them resistant to antibiotics, and easily infect the device leads from the pulse generator. Exclusive antibiotic therapy without lead extraction is therefore ineffective against most infections. It can be very difficult to distinguish between local infection and postimplant inflammation. Preliminary data indicate that these clinical situations can be distinguished by a combination of positron emission tomography and computed tomography. If validated, this approach would help in selecting the appropriate therapy in each case: lead extraction for pocket infection and symptomatic treatment for postimplant inflammation. It is nevertheless important to bear in mind that positron emission tomography does not distinguish between inflammation and infection, and findings should therefore be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation. It is essential to carefully evaluate the need for device replacement. In some studies, up to a third of patients did not require a new device. When a new device is needed, it should be implanted on the opposite side of the chest to the original device after new blood cultures confirm the elimination of any initially blood-culture-positive infection. Leads should be extracted percutaneously, even when large vegetations are present. This process can lead to complications, and should therefore be undertaken by experienced practitioners. In centers with a high patient volume, there is a very high probability of a successful, complication-free outcome. Surgical extraction is associated with more complications, related not only to the procedure itself but also to the patient’s age and comorbidities. In the early years of treating cardiac device infection, surgery was recommended when large vegetations were present, but a large vegetation is no longer considered a contraindication for percutaneous extraction. Bacterial vegetations released to the right circulation can cause pulmonary embolisms, but these tend to be asymptomatic and are less aggressive than surgery. It is important to adhere to recommended timings for the antibiotic treatment, which will obviously be guided by an antibiogram when blood cultures are positive. Antibiotic treatment should be maintained for 10 to 14 days for local infection, 14 days for systemic infection, and 4 to 6 weeks for endocarditis. When blood cultures are negative, the antimicrobials used should be active against the most frequent causes of cardiac device infection: coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus. Several of these observations are reinforced by the results of an excellent study published by Gutiérrez Carretero et al. in Revista Española de Cardiologı́a. The study presents experience with Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017;70(5):320–322

Journal Title: Revista espanola de cardiologia

Year Published: 2017

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!