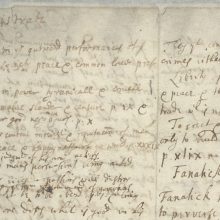

Photo from archive.org

might have been critical in helping them hold fragile families together. Similarly, the focus on the household means that we do not see the social and cultural structures and institutions—the… Click to show full abstract

might have been critical in helping them hold fragile families together. Similarly, the focus on the household means that we do not see the social and cultural structures and institutions—the church, the press, even the middle classes—through which breadwinner norms were created and replicated. Griffin is surely right to argue that low wages and limited opportunities not only reflected but reinforced women’s low status (294), but she does not explore the role that employers or trade unions played here. Yet this, of course, may well be a consequence of the source material and the autobiographers’ priorities and preoccupations. Griffin adds a vibrant and compelling account of the subjective meaning and experience of working-class family life to the account offered by historians who have examined more conventional statistical material on mortality, bodies, and nutrition. The book has already deservedly attracted a significant audience beyond the academy. With its authoritative, accessible style, it will surely introduce many new students to the rich resources to be found in nineteenthcentury life writing and even to the human possibilities of economic history. The image of Agnes Cooper’s father taking his meal to eat alone so that his hungry children would not stare at him (216) is not easily forgotten.

Journal Title: Journal of British Studies

Year Published: 2021

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!