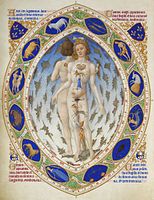

Photo from wikipedia

(143–44), he makes sweeping claims based on scant evidence. Historians of leprosy, hospitals, and public health alike have queried the extent towhich such a framing of medieval leprosy is justifiable.… Click to show full abstract

(143–44), he makes sweeping claims based on scant evidence. Historians of leprosy, hospitals, and public health alike have queried the extent towhich such a framing of medieval leprosy is justifiable. Though Jankrift cites Carole Rawcliffe (2006), he does not seem to have engaged substantially with the extensive work on medieval leprosy that has been done over the past two decades. François-Olivier Touati (1998) and Luke Demaitre (2007), for instance, are included in the bibliography but only briefly referenced in the literature review. The book’s achievement is somewhat marred by bibliographic lacunae in several fields. Though Rawcliffe’s work on leprosy is cited, for instance, her more recent work on urban public health is not (Urban Bodies [2014]). Jankrift’s view that, in the absence of central regulations, urban authorities were either unconcerned about threats to public health or powerless to deal with them ignores much research of the last decade (133). Guy Geltner, for instance (most recently 2018), is missing from the bibliography entirely. In several places, Jankrift acknowledges the importance of material and archaeological evidence and the valuable contributions that climate research can make to historians of premodern disease, particularly. This being the case, the omission of the work of Monica H. Green (2014) and Bruce S. Campbell (2016) is surprising. Some of Ann Carmichael’s valuable work is cited, but not her conspicuously relevant contributions on the language of plague treatises (2008), or on the persistence of plague from the late medieval to the early modern period (2014). Lester K. Little’s important 2011 article on the scientific identification of historical plagues is another notable absence. It may seem churlish to pick out such absences in an extensive bibliography. However, Jankrift’s work takes its place in a rich and rapidly developing field, and its arguments could have been both strengthened and contextualized by taking these recent works into account. Despite these omissions, the monograph is an impressive work. It represents the fruits of wide-ranging and thorough engagement with archival sources, and should be valuable to historians of late medieval and early modern cities as well as of medicine and public health.

Journal Title: Central European History

Year Published: 2021

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!