Photo from wikipedia

ConspectusProtein engineering has emerged as a powerful methodology to tailor the properties of proteins. It empowers the design of biohybrid catalysts and materials, thereby enabling the convergence of materials science,… Click to show full abstract

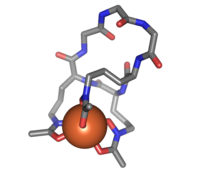

ConspectusProtein engineering has emerged as a powerful methodology to tailor the properties of proteins. It empowers the design of biohybrid catalysts and materials, thereby enabling the convergence of materials science, chemistry, and medicine. The choice of a protein scaffold is an important factor for performance and potential applications. In the past two decades, we utilized the ferric hydroxamate uptake protein FhuA. FhuA is, from our point of view, a versatile scaffold due to its comparably large cavity and robustness toward temperature as well as organic cosolvents. FhuA is a natural iron transporter located in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli (E. coli). Wild-type FhuA consists of 714 amino acids and has a β-barrel structure composed of 22 antiparallel β-sheets, closed by an internal globular "cork" domain (amino acids 1-160). FhuA is robust in a broad pH range and toward organic cosolvents; therefore, we envisioned FhuA to be a suitable platform for various applications in (i) biocatalysis, (ii) materials science, and (iii) the construction of artificial metalloenzymes.(i) Applications in biocatalysis were achieved by removing the globular cork domain (FhuA_Δ1-160), thereby creating a large pore for the passive transport of otherwise difficult-to-import molecules through diffusion. Introducing this FhuA variant into the outer membrane of E. coli facilitates the uptake of substrates for downstream biocatalytic conversion. Furthermore, removing the globular "cork" domain without structural collapse of the ß-barrel protein allowed the use of FhuA as a membrane filter, exhibiting a preference for d-arginine over l-arginine.(ii) FhuA is a transmembrane protein, which makes it attractive to be used for applications in non-natural polymeric membranes. Inserting FhuA into polymer vesicles yielded so-called synthosomes (i.e., catalytic synthetic vesicles in which the transmembrane protein acted as a switchable gate or filter). Our work in this direction enables polymersomes to be used in biocatalysis, DNA recovery, and the controlled (triggered) release of molecules. Furthermore, FhuA can be used as a building block to create protein-polymer conjugates to generate membranes.(iii) Artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs) are formed by incorporating a non-native metal ion or metal complex into a protein. This combines the best of two worlds: the vast reaction and substrate scope of chemocatalysis and the selectivity and evolvability of enzymes. With its large inner diameter, FhuA can harbor (bulky) metal catalysts. Among others, we covalently attached a Grubbs-Hoveyda-type catalyst for olefin metathesis to FhuA. This artificial metathease was then used in various chemical transformations, ranging from polymerizations (ring-opening metathesis polymerization) to enzymatic cascades involving cross-metathesis. Ultimately, we generated a catalytically active membrane by copolymerizing FhuA and pyrrole. The resulting biohybrid material was then equipped with the Grubbs-Hoveyda-type catalyst and used in ring-closing metathesis.The number of reports on FhuA and its various applications indicates that it is a versatile building block to generate hybrid catalysts and materials. We hope that our research will inspire future research efforts at the interface of biotechnology, catalysis, and material science in order to create biohybrid systems that offer smart solutions for current challenges in catalysis, material science, and medicine.

Journal Title: Accounts of chemical research

Year Published: 2023

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!