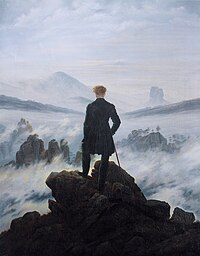

Photo from wikipedia

Perhaps for good reason and to the relief of our readers, not one of the essays in this issue takes up the account of Romanticism discernible in Freud’s Civilization and… Click to show full abstract

Perhaps for good reason and to the relief of our readers, not one of the essays in this issue takes up the account of Romanticism discernible in Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents—according to which Romanticism would be the name for a naive, putatively Rousseau-inspired discontent with civilization. Freud refers to this as “the contention that what we call our civilization is largely responsible for our misery, and that we should be much happier if we gave it up and returned to primitive conditions” (38). But if that is one way of defining Romanticism—Romanticism as shorthand for discontent with civilization—then what would be the discontents of discontent? If none of the contents of this issue accuse civilization, they do offer various critiques of globalization understood as a universalization one cannot refuse. Choosing “Romanticism and Its Discontents” as a rubric for the 2016 NASSR Conference at the University of California, Berkeley, was the first, and easiest, decision of its organizers. If, on the one hand, it was meant as a subtle gesture, an “open secret” of resistance to the imperative of institutional self-reproduction that academic conferences represent, on the other, it expressed a wish to highlight “the part of those that have no part” (70), to adopt Jacques Rancière’s formula of democratic politics: not only populations, but also those parts of experience or perception relegated to the outside of representation. If this wish itself risks reproducing a familiarly Romantic program of inclusion, the thought experiments presented here tend to disregard rhetorics of inclusion in favor of attention to dispersion: to atmosphere, climate, sound, echo, tactility, and ephemerality. In this latter sense, “discontents”—famously used by James Strachey to translate Freud’s German Unbehagen (in French, malaise)—might be understood as unhappiness with the sense of containment implicit in (dis) “contents.” Rather than a table of “contents,” then, the program of “Romanticism and Its Discontents” might be read as an attempt to limn the shape or feel of those bounding lines that police interiors and exteriors, texts and contexts. Denise Ferreira da Silva’s critique of the “inclusive” logic of universality—as if the racial other were patiently and passively waiting to be invited to the party—forms the basis of one trajectory of the “discontent” explored at the conference: the non-reversibility of inclusion, and the asymmetry of “universal access.” In her keynote address, “The Racial

Journal Title: European Romantic Review

Year Published: 2017

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!