Photo from wikipedia

Pathologists have known for centuries that calcific deposits formed in vascular tissues such as the aortic valve. Calcific deposits are hard like bone and have often been described as such.… Click to show full abstract

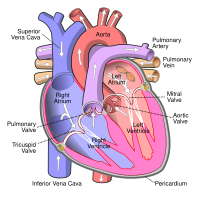

Pathologists have known for centuries that calcific deposits formed in vascular tissues such as the aortic valve. Calcific deposits are hard like bone and have often been described as such. In his ‘History of Animals’, Aristotle remarked that often in oxen and particularly in horse, the heart ‘has a bone inside it’.1 And in 1646, the French professor of medicine Lazare Riviere described his post-mortem examination of a patient's diseased aortic valve by remarking that it resembled ‘a cluster of hazelnuts’.2 Today, aortic valve calcification remains the most common cause of valve stenosis3,4 and is present in some 26% of the population over the age of 65, and as many as half of those over 85.5 Well into the 20th century, the formation of calcific lesions was believed to be a normal, passive process associated with aging. In the early 1990s, however, this attitude began to change when Bostrom et al . identified bone morphogenetic protein-2a in calcified human carotid arteries.6 Later, in addition to descriptions of standard ‘dystrophic calcification’, histological studies identified endochondral bone formation in heavily calcified aortic valves7 and gene expression analyses demonstrated up-regulation of several bone-specific genes.8 The biological case for bone formation in the vascular system had been established, but how closely do calcific lesions resemble bone as a material? To understand bone, biomineralization researchers have long utilized non-quantitative physical science techniques, including analytical electron microscopy, to examine tissues ex vivo . Such analyses can sometimes reveal more than standard histological stains that often only detect the presence of calcium and/or phosphate. …

Journal Title: European Heart Journal

Year Published: 2017

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!