Photo from wikipedia

To the Editor: We read with interest the article published in a recent issue of Critical Care Medicine by Ahmed et al (1), in which the timing of tracheostomy in… Click to show full abstract

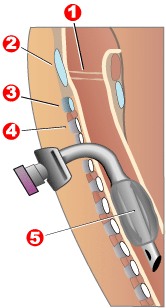

To the Editor: We read with interest the article published in a recent issue of Critical Care Medicine by Ahmed et al (1), in which the timing of tracheostomy in pediatric patients was examined. This review included eight retrospective studies, subgroup analyzing with age and length of mechanical ventilation (MV) as a potential confound factor. The study suggested that early tracheostomy may provide potential clinical benefits in pediatric populations. This is a very interesting review with strong methodology, but there are few additional points for clinicians to bear in mind. The tracheostomy practice and the discussion of the timing for the children should not be straightforward. The timing of the tracheostomy could be influenced by medical and nonmedical factors, such as disease etiology and comorbidity, post-surgery, parental thoughts, and healthcare resource availability. Those factors are, generally, difficult to be captured in a retrospective study and possibly strongly affect the effect measurements by selection and information biases. Almost no studies included in this review get into the details of the disease etiology or those factors. For instance, how can we explore the effect of early tracheostomy without considering the difference between the patient early-tracheostomized with known upper airway anatomical obstruction and the patients late-tracheostomized for failed extubation due to such as severe brain injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome recovering slowly over weeks? The severity of illness may also differ between the early and late tracheostomy cohorts. For example, we could assume that less-severe patients may inherently be less-represented in the late-tracheostomized groups, which could explain the part of the results. We also need to consider the nonclinical or nonventilatory issues (i.e., parental support, resource availability outside of PICUs, workload management in PICUs, and limitation of treatment such as palliative care) to discuss the timing of tracheostomy, particularly with prolonged MV (PMV) in PICU patients comprehensively. Studies reported that the majority of PICU patients require less than 10–14 days of MV (2, 3). However, in our recent systematic review of pediatric definition of PMV (4), 21 days of MV days were the most widely used in the existing pediatric studies. Furthermore, our recent cross-sectional survey in Canada revealed that physicians remain reluctant to recommend tracheostomy for children requiring PMV due to lung disease alone at 21 days of MV (5). This evidence may indicate that there is a potential discrepancy between actual physician practice toward tracheostomy for PMV and the clinical knowledge they have. To sum, the pediatric tracheostomy practice and the possible future study design needs to be examined from multiple points of view; definition of PMV, healthcare resource burden including such as payment or insurance system, patient and social profiles, and knowledge translation. A comprehensive understanding of the updated cohort should be central in this sense (https://longventkids.ca/, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04112459). This may lead us to understand which cohort may receive the largest benefit of early tracheostomy and vice versa, and what kind of outcome measurements we should see in the future interventional studies. Dr. Jouvet disclosed that medical devices were leant by Hamilton Medical, Philips, and Dymedso. Dr. Emeriaud’s institution received funding from Fonds de recherche du Québec Santé and Maquet Critical Care (financial support for a research study). Dr. Kawaguchi is supported by Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Journal Title: Critical Care Medicine

Year Published: 2020

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!