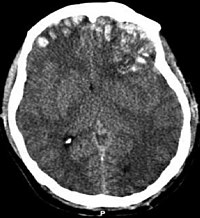

Photo from wikipedia

Abstract Background Individuals in violent intimate relationships are at a high risk of sustaining both orthopaedic fractures and traumatic brain injury (TBI), and the fracture clinic may be the first… Click to show full abstract

Abstract Background Individuals in violent intimate relationships are at a high risk of sustaining both orthopaedic fractures and traumatic brain injury (TBI), and the fracture clinic may be the first place that concurrent intimate partner violence (IPV) and TBI are recognized. Both IPV and TBI can affect all aspects of fracture management, but prevalence of TBI and comorbid TBI and IPV is unknown. Questions/purposes (1) What are the previous-year and lifetime prevalence of IPV and TBI in women presenting to an outpatient orthopaedic fracture clinic? (2) What are the conditional probabilities of TBI in the presence of IPV and the reverse, to explore whether screening for one condition could effectively identify patients with the other? (3) Do patients with TBI, IPV, or both have worse neurobehavioral symptoms than patients without TBI and IPV? Methods The study was completed in the fracture clinic at a community Level 1 trauma center in Southern Ontario from July 2018 to March 2019 and included patients seen by three orthopaedic surgeons. Inclusion criteria were self-identification as a woman, age 18 years or older, and the ability to complete forms in English without assistance from the person who brought them to the clinic (for participant safety and privacy). We invited 263 women to participate: 22 were ineligible (for example, they were patients of a surgeon who was not on the study protocol), 87 declined before hearing the topic of the study, and data from eight were excluded because the data were incomplete or lost. Complete data were obtained from 146 participants. Participants’ mean age was 52 ± 16 years, and the most common diagnosis was upper or lower limb fracture. Prevalence of IPV was calculated as the number of women who answered “sometimes” or “often” to direct questions from the Woman Abuse Screening Tool, which asks about physical, emotional, and sexual abuse in the past year or person’s lifetime. The prevalence of TBI was calculated as the number of women who reported at least one head or neck injury that resulted in feeling dazed or confused or in loss of consciousness lasting 30 minutes or less on the Ohio State University Traumatic Brain Injury Identification Method, a standardized procedure for eliciting lifetime history of TBI through a 3- to 5-minute structured interview. Conditional probabilities were calculated using a Bayesian analysis. Neurobehavioral symptoms were characterized using the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory, a standard self-report measure of everyday emotional, somatic, and cognitive complaints after TBI, with total scores compared across groups using a one-way ANOVA. Results Previous-year prevalence of physical IPV was 7% (10 of 146), and lifetime prevalence was 28% (41 of 146). Previous-year prevalence of TBI was 8% (12 of 146), and lifetime prevalence was 49% (72 of 146). The probability of TBI in the presence of IPV was 0.77, and probability of IPV in the presence of TBI was 0.36. Thus, screening for IPV identified proportionately more patients with TBI than screening for TBI, but the reverse was not true. Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory scores were higher (more symptoms) in patients with TBI only (23 ± 16) than those with fractures only (12 ± 11, mean difference 11 [95% CI 8 to 18]; p < 0.001), in those with IPV only (17 ± 11) versus fractures only (mean difference 5 [95% CI -1 to -11]; p < 0.05), and in those with both TBI and IPV (25 ± 14) than with fractures only (mean difference 13 [95% CI 8 to 18]; p < 0.001) or those with IPV alone (17 ± 11, mean difference 8 [95% CI -1 to 16]; p < 0.05). Conclusion Using a brief screening interview, we identified a high self-reported prevalence of TBI and IPV alone, consistent with previous studies, and a novel finding of high comorbidity of IPV and TBI. Given that the fracture clinic may be the first healthcare contact for women with IPV and TBI, especially mild TBI associated with IPV, we recommend educating frontline staff on how to identify IPV and TBI as well as implementing brief screening and referral and universal design modifications that support effective, efficient, and accurate communication patients with TBI-related cognitive and communication challenges. Level of Evidence Level II, prognostic study.

Journal Title: Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research

Year Published: 2022

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!