Photo from wikipedia

The care system for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes, but is not limited to, interactions between and choices made by health and social care professionals, patients, and… Click to show full abstract

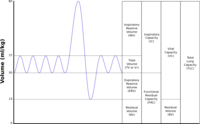

The care system for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes, but is not limited to, interactions between and choices made by health and social care professionals, patients, and their families and carers. Actors within this system will have varying degrees of agency, be constrained by factors including culture and economics, and have varying and potentially conflicting motivations. This sort of complex network can be thought of as a kind of ecosystem, which in the case of COPD is anything but healthy. A majority of patients with the condition miss out on basic aspects of care, such as evidence-based smoking cessation support, pulmonary rehabilitation, and effective selfmanagement, with substantial unwarranted variation in outcomes (1) and considerable unmet need among breathless patients (2). Developing the analogy, there is growing understanding of the wide effect that apex predators have across ecosystems; for example, by reducing herbivore and mesopredator numbers, apex predators can increase diversity in populations of small mammals and plant species (3). Poor COPD care in part reflects nihilism about the effectiveness of treatment, but evidence now shows clearly that in appropriately selected patients with the condition, lung volume reduction (LVR) surgery and endobronchial valve placement can have substantial benefits on lung function, exercise capacity, health status, and even survival (4–9). LVR procedures thus provide a system incentive to ensure that patient assessment, and care in general, is optimized so that those patients who are eligible can be identified and benefit. As such, LVR procedures have the potential to take on this “apex” role in the COPD care ecosystem, providing a treatment that, although only a proportion of patients are eligible, still provides a “pull factor” that could drive up standards of care more broadly. The recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence COPD guideline update (10) outlines a stepwise system approach to evaluation for LVR (Table 1). At the end of pulmonary rehabilitation, patients’ condition and their pharmacotherapy should have been optimized as far as is possible. If at that point they are still limited by breathlessness, the plausibility of LVR should be considered in all individuals. In the absence of obvious contraindications such as frailty or multimorbidity, a respiratory assessment including computed tomography thorax and lung function testing should be performed. Where emphysema and significant hyperinflation are identified, suggesting LVR is a possibility, a review by an LVR multidisciplinary team, able to assess technical suitability and weigh different options to establish whether any LVR approach is likely to be beneficial, should be considered. Obviously, to get to this final point, the healthcare system requires breathless patients with COPD actually to be offered and be able to access pulmonary rehabilitation, receive smoking cessation support, and have appropriate pharmacotherapy. Most studies of LVR with endobronchial valves have used the Zephyr valve (4–9, 11). This contains a duckbill valve inside a nitinol/silicone frame and is held in place against the airway mucosa, as the device expands when deployed. A recent metaanalysis of trials using the Zephyr device found that in patients without collateral ventilation, valve placement improved residual volume by 0.57 L (95% confidence interval, 20.71 to 20.43), FEV1 by 21.8% (17.6–25.9%), and 6-minute-walk test by 49 m (95% confidence interval, 32–66 m) (12). An alternative device, the Spiration valve, constructed of nitinol coated with polyurethane, has an umbrella design and, when deployed, fixes onto the airway wall with five anchor hooks. Initial, unsuccessful clinical trials with this valve did not use the whole-lobe approach to treatment (13), which is now acknowledged to be necessary for endobronchial valve treatment to be effective. In this issue of the Journal, Criner and colleagues (pp. 1354–1362) describe the results of the EMPROVE study, which investigated the effect of lobar occlusion with this valve in patients with heterogeneous emphysema, hyperinflation, and intact interlobar fissures assessed as .90% intact on computed tomography bounding the target lobe (14). In a multicenter study, 172 participants were randomly assigned 2:1 to valve placement or usual care. In terms of technical efficacy, 75% of those treated had at least a 350-ml reduction in target lobe volume, and 40% had complete atelectasis of the target lobe. There was 101 ml between group difference in change in FEV1 at 6 months, favoring valve placement accompanied by a between group change in residual volume of 361 ml. Health status and breathlessness improved, but there was no effect on walking distance. Safety outcomes were similar to those seen in previous valve studies: 12.4% of patients treated with valves experienced a serious pneumothorax. Of these, around two thirds required one or more valve to be removed, although in half of these cases it was possible to replace the valves subsequently with good long-term outcomes. Two thirds of pneumothoraces occurred within 3 days of the procedure, underlining the importance of in-patient observation for 3 nights after endobronchial valve placement. By 12 months, 9% of treated and 7% of control patients had died. Only one death occurred within 3 months of the procedure (from sepsis at 26 d), and only one death, from a lung abscess in the target lobe 353 days postprocedure, was judged as likely to be related to the device. There are some technical issues to the study. The study did not include a sham procedure (5) and so was unblinded. This is less

Journal Title: American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

Year Published: 2019

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!