Photo from wikipedia

this work does serve an informative purpose for a reading public as popular history, but it will not often appear shelved in academic offices. Instead, many will rely on T.… Click to show full abstract

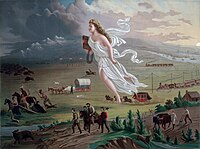

this work does serve an informative purpose for a reading public as popular history, but it will not often appear shelved in academic offices. Instead, many will rely on T. R. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (New York, 1968), in which the noted historian devotes many pages to Houston, his many accomplishments, and his darker, paradoxical side. In many ways, Fehrenbach was a traditional, or consensus, historian, unlike a more recent group whose work shows revisionist impulses—an example is Gary Clayton Anderson’s The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820–1875 (Norman, Okla., 2005). Houston winds and works his way through Anderson’s book, too, and it comes as little surprise that this Sam Houston hardly resembles the one featured in Rozelle’s text. Such is the historiography and the myriad interpretations associated with Houston, his legend, and his myth, along with the turbulent era in which he lived. The biographical and historical battle of the books thus continues, never to be won. Houston was Andrew Jackson’s disciple, and they shared similar ideas relative to westward expansion, slavery, Mexico, and the future of the Union. But a young Houston had lived among the Cherokees, and this experience drove a wedge into the relationship between Houston and Jackson because of Jackson’s determination to dispossess Natives of their land. Throughout Houston’s political life, he frequently spoke in their behalf. Many white southerners hated him for this defense of Native interests. Texas beckoned to Houston as Anglos moved in the direction of revolt from Mexican rule; in the most decisive battle, his heroics at San Jacinto, defeating theMexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna, boostedHouston quickly to military hero and ensured his political career in the Lone Star republic, where he twice served as president. After the U.S. annexation of Texas, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, as the nation began to split over the issue of slavery. He supported Henry Clay’s Compromise of 1850, which alienated Houston from southern colleagues and a host of Texans as well. A slave owner, Houston was elected governor in 1859 but was soon at odds with secessionists in Texas. He refused to sign a loyalty oath to the Confederacy, because, like Jackson before him, Houston wanted the Union to remain intact. Because of this conviction, he resigned as governor in 1861. His political life ended with this victory of conscience, as he was exiled to private life. Perhaps his antisecession, pro-union beliefs, after all, made him even a greater hero than did his victory at San Jacinto.

Journal Title: Journal of Southern History

Year Published: 2019

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!