Photo from wikipedia

TO THE EDITOR: We have read with great attention the article by Dempsey and colleagues3 (Dempsey RJ, Varghese T, Jackson DC, et al: Carotid atherosclerotic plaque instability and cognition determined… Click to show full abstract

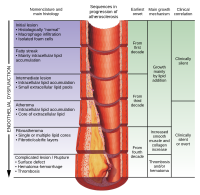

TO THE EDITOR: We have read with great attention the article by Dempsey and colleagues3 (Dempsey RJ, Varghese T, Jackson DC, et al: Carotid atherosclerotic plaque instability and cognition determined by ultrasound-measured plaque strain in asymptomatic patients with significant stenosis. J Neurosurg 128:111–119, January 2018). The authors presented a stimulating study that describes “the use of ultrasound measurements of physical strain within carotid atherosclerotic plaques as a measure of instability and the potential for vascular cognitive decline, microemboli, and white matter hyperintensities (WMHs).” Subsequently, the same group demonstrated that atherosclerotic vascular cognitive decline may be modified by removal of the unstable plaque.2 In that earlier study,3 the authors stated in their results that “the degree of strain instability measured within the atherosclerotic plaque directly predicted vascular cognitive decline in these patients thought previously to be asymptomatic according to classic criteria. Furthermore, 26% of patients showed microemboli, and patients had twice as much white matter hyperintensity as controls.” As our lead author (A.N.) is involved in studying the natural course of ischemic WMHs and explaining the relationship between brain revascularization and the course of ischemic WMHs,5,6 he has uncovered some interesting points that have raised several questions, and we would like to obtain answers from experts3 that may be helpful in our current and future research. Based on a thorough survey of the English literature,1–7 evidently WMHs have been related to cognitive decline, and the changes in ischemic WMHs over time can be dynamic4-6 or partially reversible in patients with carotid artery stenosis.7 Previously, we established a relationship between brain revascularization and the course of ischemic WMHs.5,6 Therefore, we recommended further prospective studies to search for a relationship between WMH changes and functional neurological or neurocognitive data.6 Herein, we would like to ask the authors3 the following questions. 1. Have they3 done follow-up neuroimaging to assess the course of WMHs (improvement, unchanged, worsened, or fluctuating)? What about the time factor? 2. Did the authors3 find remarkable WMH changes in patients without evidence of microemboli? We would like to know the details of these WMHs. 3. Are the degree of strain instability and the surprising amount of WMH changes considered as direct predictors for the vascular cognitive decline in their cases? 4. What about the distribution of the WMHs (periventricular, deep WMHs, cortical)? 5. Did the authors3 have a fluctuating cognitive readout in their population? 6. We completely agree with the authors in their belief that “the presence of some emboli in other distributions and the symmetry of the WMHs showed that the presence of plaque instability not only suggests ipsilateral emboli but also represents a marker of advanced systemic largeand small-vessel disease.”3 Can we correlate that with the WMH improvement following direct extracranial-intracranial bypass suregery?5,6 Finally, we appreciate the authors’ contributions to neurosurgery, and we consider the above-mentioned study3 as a fundamental reference in our current research. Thus, we are looking forward to receiving their valuable comments and additional data.

Journal Title: Journal of neurosurgery

Year Published: 2018

Link to full text (if available)

Share on Social Media: Sign Up to like & get

recommendations!